Lever #3: Exercise — Part Two: Strength

Why exercise is the most effective way to improve our lives, three rules for strength training & The Minimalist’s Guide to Strength.

“If you have the aspiration of kicking ass when you’re 85, you can’t afford to be average when you’re 50.” — Peter Attia

As I revised, edited, and made some additions to what was intended to be the final article introducing exercise, it became far too long to release altogether. As such, what I intended to be one article has turned into a three-part series. We’ll cover strength training today and then stability, mobility, and flexibility next week.

Without further ado, let's pick up where we left off last week by introducing strength training.

Strength

In an effort to avoid duplication of content, I’ll begin by recommending that you read the Building Muscle subsection of a previous article I wrote titled DEXA Scans: My Results & Three Elements Essential to Longevity if you haven’t already. I outline the importance of building strength, suggest guidelines for doing so safely, and provide a general strength, or resistance, training framework for beginner, intermediate and advanced levels.

We’ll continue to build upon that foundation and deepen our knowledge of strength training here by addressing two key questions: 1) Why train for strength? and 2) How to train for strength?

Strength Training: The Why

The reason why you should train for strength is twofold. One, increased strength will decrease your risk of mortality, especially as you age. Two, increased strength and muscle mass will increase your quality of life, both now and especially in later stages of life.

To tie in what we learned last week with the idea that each sub-lever of exercise decreases our risk of mortality and improves our quality of life in different ways, we’ll look at a study that showed improving cardiorespiratory health, which can be done through aerobic exercise, is the most effective method of extending longevity.

Individuals who were classified as having low cardiorespiratory fitness decreased their risk of all-cause mortality by 34% when they went from the low to the medium group and by an astonishing 42% when they went from the low to the high group. Remember what I said last week about exercise being more effective than any drug? There isn’t a pill that comes close to increasing our lifespan and improving our healthspan as much as a combination of all four forms of exercise does.

Linking this back to strength, if your sole focus is to find the minimum effective dose (MED) required to live longer aerobic exercise will likely give you the biggest bang for your buck. However, the group that had both high cardiorespiratory fitness and high strength found a 47% reduction in mortality risk. You may be thinking that having to strength train if you hate it, isn’t worth the extra 5% reduction in risk.

However, I urge you to consider one qualitative factor that this study did not: quality of life. Remember, our goal isn’t just to live for longer, especially if we can’t use that additional time to do the things we love due to a compromised mental or physical state.

Strength is an essential part of being able to do the things you love now well into your 80s or 90s from hobbies, playing with your future grandkids, and performing the basic activities of daily living (ADLs) on your own. Now that I hope I’ve convinced you as to why strength training is important, let’s move on to the how.

Strength Training: The How

In building strength there are three basic rules that, if followed, will yield massive results and benefit you greatly over the long term. They’ve been ordered in the manner in which I believe they should be prioritized, especially the first one.

Rule #1: Don’t get hurt

This seems like a no-brainer, but in practice when most people begin strength training they throw this notion out the window in favour of trying to throw up heavy weights or performing more volume, defined as the number of sets multiplied by the number of repetitions (reps) per set than they should.

Drop your ego at the door, start by lifting excessively light weight and record yourself to ensure your form matches the gold standard. As there are countless instructional videos online, I won’t get into the weeds of proper form here. As a rule of thumb, a high view count generally equates to a reliable source. In addition, I’ve linked a few recommendations in the Exercise Resources section at the bottom of this article.

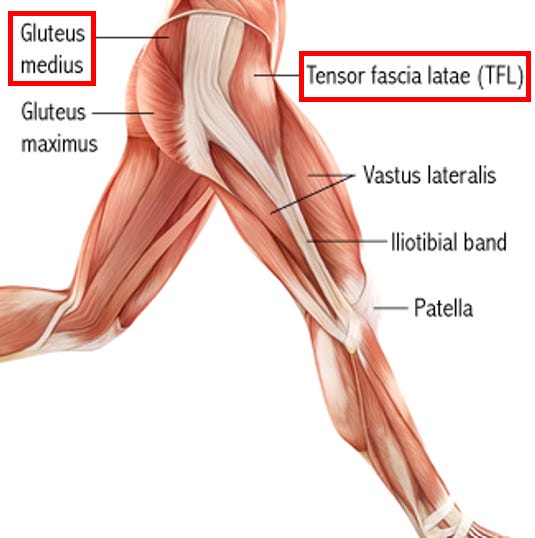

Another key part of avoiding injury, other than ensuring proper form, is warming up properly. If engaging in lower body exercises, such as squats and deadlifts, it’s essential to properly activate your gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae (TFL) (see red boxes above).

Of course, it’s also important to ensure you’re properly warming up the other major muscles in your legs (gluteus maximus, quadricep muscles, etc.), joints (hips, knees, ankles), and tendons, however, we generally cover these whereas the two muscles mentioned above often go missed.

Ensuring you incorporate a few warm-up sets with light to moderate weight and leveraging some of the movements linked at the bottom (glute activation series, full-body mobility routine) provides a great starting place.

For upper body movements, such as bench press and overhead press, the shoulders and elbows should be the focal points of your warm-up routine. I’ve also linked some upper body warm-up routines at the bottom of the article.

Rule #2: Focus on the main lifts — squat, deadlift, bench, overhead press (OHP)

Focusing on these four main lifts is a perfect application of the 80/20 Principle, which I first wrote about in The Longevity Framework. Having an exercise program that is centered around these four exercises is quintessential to designing a highly effective strength program.

Incorporate strength training into your exercise regimen at least three times per week (this is the MED), focus on the four main lifts, and then add in some of the time-tested ancillary movements such as push-ups, pull-ups, dips, lunges, kettlebell swings, planks, and bicycle crunches.

We’ll get into the weeds of strength training in the future, for those who are interested, but if not sticking to these simple movements is all you really need to become well-rounded and proficient from a strength standpoint.

If you’ve never done these lifts before, you might feel a little overwhelmed — hell, I still get in my own head and question my form at times. Don’t feel the need to go out and learn all four at once. Start slow and learn them one at a time by leveraging the power of the Internet.

With an instructional video on proper technique, a phone to record yourself, and a broomstick, you can gain comfort over how to perform these lifts from your living room before stepping foot in a gym.

The Minimalist’s Guide to Strength Training

For those who don’t have enough time or those who are looking to really minimize their time spent on resistance training, the program outlined below will derive a large majority of benefits for a very small investment of time.

I was introduced to this minimalistic routine by Pavel Tsatsouline, the Russian fitness instructor largely accredited with bringing the kettlebell to the Western world and known for training SPETSNAZ, Navy SEALs, and everyone in between.

Although he has authored a variety of books that outlay various training protocols with different aims, he often sticks to a minimalist practice of two movements: Kettlebell Swings + Dips (or push-ups). Perform this combination of a hip hinge (KB swing) and push (dip, push-up) three times per week. Each workout should consist of a total of 75 KB swings and roughly the same number, give or take, of push-ups or dips.

Pavel argues that the KB swing is the most beneficial exercise we can do as it trains functional strength and power, engages and develops the mitochondria in Type 2 (fast-twitch) muscle fibres, strengthens connective tissue, and targets our anaerobic system.

This sentiment is echoed by Tim Ferriss in The 4-Hour Body as he advises that the swing can help you build a “superhuman posterior chain”. Adding in a push movement, the dip or push-up, covers what’s missing by building up your chest, shoulders, and triceps.

Throw in a few runs, or another aerobic exercise of your choice, into each week and call it a day. You may not squeeze the maximum amount of benefit possible from exercise with this protocol, but this is probably the best option if you’re always in a time crunch, especially if you look at the ratio of time invested to potential results.

This routine is short, sweet, and unmatched in the punch it packs for the time it demands.

Rule #3: Challenge yourself and stay motivated.

Everyone is different. At the end of the day, finding a way to stay motivated and be disciplined when you’re not feeling motivated, is your responsibility. You must hold yourself accountable, no one can do that for you.

However, setting both short- and long-term goals and challenges for yourself is certainly a useful tool to increase both motivation and commitment.

In the realm of strength training, a tactic called progressive overload allows you to improve every time you strength train and ensures that in a year from now, you will be stronger than you are today.

Progressive overload provides three simple ways to gradually improve each time you strength training whether you’re using bodyweight, weights, or bands: Increase your 1) Weight, 2) Frequency, or 3) Volume.

While looking to increase weight, microplates (2.5 or 5 pounds) are of great use. For example, in week one of a strength program, you squat with 135lbs. Next week you can add a 2.5lb plate to each side of the bar for a total of 140lbs. This small increment won’t make the total weight feel much heavier but, over time, will massively contribute to increasing your strength. You will eventually hit a plateau where you may need to back off and stay at the same weight for a couple of weeks before being able to add more.

Increasing frequency consists of performing a certain exercise for more sessions or increasing the number of times you strength train in general, in a given week. Say you begin strength training and after 5 weeks of increasing the weight on your squat by 5-10lbs each week, you hit a plateau. You may decide to stick with the same weight, but squat twice a week instead of once in order to break through that plateau.

Lastly, increasing volume (number of sets x number of reps) is simply increasing the number of sets and/or reps for an exercise during a strength training session. Using our squat example, you may decide to increase from 3 sets of 10 reps to 3 sets of 12 reps or 4 sets of 10 reps.

Progressive overload is one of the simplest and most time-tested approaches to gaining strength and building muscle volume. Having it in your repertoire of tactics will prove to be of great benefit once you see the results that applying it to your strength training can generate.

Moving Forward

Next week we’ll cover the final sub-lever of exercise: stability, mobility, and flexibility, and then tie together each sub-lever to get a snapshot of what our week looks like when we engage in a well-rounded exercise routine.

And, as always, please give me feedback on Twitter or by hitting reply to this email.

Much love,

Jack

Exercise Resources

Warm-Up

Glute Activation Series - Peter Attia

Full Body Mobility (Warm Up) Routine - Jeff Nippard

How to PROPERLY Warm Up Before Weights (total body) - Jeremy Ethier

My Upper Body Mobility Warmup Routine - Matt Ogus

Strength Training

Strong First - Pavel Tsatsouline

Recommended Books